Models are data structures that we use to define the shape of our data. You might also know them as objects, as in Object Oriented Programming, but in JavaScript everything is an Object, so it’s not clear that we are talking about something specific if we just call them objects.

The usefulness of the term “model” can be exemplified in it’s use in the Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture. The model is the part of the software that holds the data that is to be manipulated by the controller, and displayed by the view. There are several other Model-View variants, collectively referred to as MV*. The core component of all of them is the model. I’m not strictly holding the models I am talking about here to the standards of those various architectures, but I want to point out that the “model” data structure has been a useful part of web architecture for a long time.

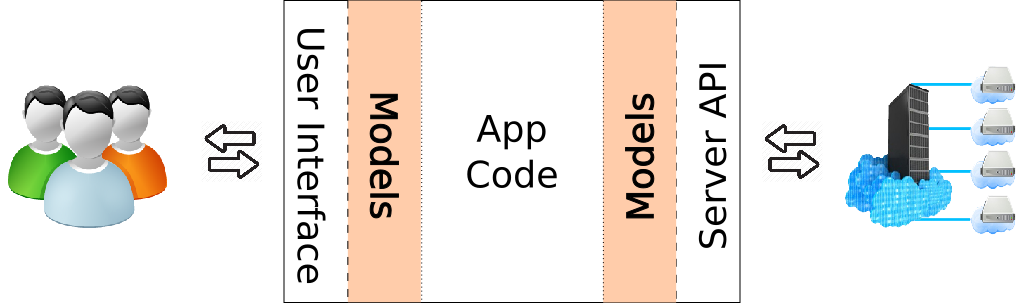

The model is the core component of the user interface. It is the one place where you can filter and manage all of the data that passes through your application. You can do all of your data validation in the model. And you can set the properties in your models to have reasonable defaults so that you can minimize the amount of null checking and defensive code you will need to write throughout your application; and also prevent showing strange values like null, NaN, undefined, etc… to your users.

Of course, once you begin using models as the fundamental data structure in your code, you will begin to see how useful it is to move beyond simply defining properties on the model, and start adding functions to your models that increase the convenience of using them everywhere. Just remember to keep the application logic isolated from the model itself. Any functions that the model carries with it should specifically serve the purpose of reading from or writing to the model’s properties.

Some useful functions for a model would be:

- validation - to validate the data being assigned to each field in the model

- comparison - to easily check if two models are equal to each other

- formatting - to format certain pieces of the data for the UI (e.g. date, address, full name, etc…)

Some things we should not do in models are:

- call the server

- control or manipulate the user interface

- use it for anything that is not directly related to the model

A Model

So, what might a model look like? Let’s make a Person model as an example.

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

obj = obj != null ? obj : {}

this.address = obj.address != null ? obj.address : ''

this.birthDate = obj.birthDate != null ? obj.birthDate : ''

this.firstName = obj.firstName != null ? obj.firstName : ''

this.friends = obj.friends != null ? obj.friends : []

this.lastName = obj.lastName != null ? obj.lastName : ''

this.petNames = obj.petNames != null ? obj.petNames : []

}

}This simple model has six properties (address, birthDate, firstName, friends, lastName, and petNames). The constructor takes in an optional object as its only parameter.

- If the obj is undefined or null then each model property is set to its respective default value.

- If the obj is defined but a specific property on that obj is undefined or null then that respective model property is set to the default value.

- If the obj is defined and the property on that obj is defined then that respective model property is set to the property from the obj.

We could set a default value for the obj when we define it as a parameter to the constructor

constructor(obj = {}) { ... }

but null counts as a value, so if we ever pass null into the constructor all of the calls to obj.property will fail.

The end result is that we would still have to check if obj === null.

obj != null) instead of truthy comparisons (obj == null). Writing the conditionals this way allows us to put the default values on the outer right edge of the assignment statements, which makes them much easier to find when reading through the code to find out what the default value for a given property is.

Input Validation

If we wanted to validate the input, we could create a function to do that and make that part of the assignment conditional like so:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

...

this.birthDate = this.isValidDate(obj.birthDate) ? obj.birthDate : ''

...

}

isValidDate(date) {

let isValid = true

try {

const n = new Date(date).getTime()

isValid = Number.isFinite(n)

} catch (err) {

isValid = false

}

return isValid

}

}That way, if the input value is valid it is set on the model, otherwise the model property is set to the default value.

Notice that our try/catch in the isValidDate function does not throw an error. It allows a value to be returned from the function even if the input was invalid, but still alerts us to the fact that we saw data that we were not expecting. If you want to stop the app because of this - for instance, if not having a date defined in this model is a deal breaker for your app - then throw an error instead of just logging an error.

Setting a reasonable default value for dates can be tricky, and picking the right one may vary from application to application.

If you create a new date with an empty string, or NaN, e.g. x = new Date(""), then x.toString() will return “Invalid Date”, and functions like x.getMonth() will return NaN.

If you create it with no given input, it will create a date representing the time that the Date was instantiated.

If you create it with 0 or null, it will create a date of Jan 1, 1970.

And giving it a negative number will just count backwards from Jan 1, 1970.

Dates in JavaScript are generally one of the most difficult things to deal with consistently in all cases. We have to take into account things like different time-zones, different possible input formats, different default formats for different locales, etc… Until the ECMAScript standard deals with this problem correctly, dates are the one piece of data where using a 3rd party library to deal with them is easily justified.

One way to ensure that everyone knows exactly what the date should be is to represent it as an ISO formatted string in the UTC timezone (e.g. 2020-12-31T23:59:59.999Z). That way there is no guessing if it is formatted as mmddyyyy, ddmmyyyy, mmddyy, etc… Any special formatting for display should be done at the display, and the date should always be stored as an ISO UTC string. If the date truly is unspecified, the best default value is an empty string - at least that will let your code know that it received something that should not be interpreted as a date - and it can safely be displayed in the UI.

Data Formatting

Now let’s consider when we want to compile some, or all, of the model data into things that we can easily use in the UI. For example, we probably want to format the birthDate consistently everywhere we show it. Instead of writing code to do that formatting everywhere that we want to see it in the UI, we should create a function on the model to do that formatting.

class Person {

...

formatDate(date) {

let formattedDate = ''

try {

formattedDate = new Date(date).toLocaleDateString()

} catch (err) {

console.error('Person.formatDate - Invalid date: ', date)

}

return formattedDate

}

}Now, in the rest of our code, we could call this function every time we want to display the person’s birth date. I say could because we can potentially make this better by adding a property called something like formattedBirthDate to our Person model, and then only calling this function once when the Person is instantiated. Then we can just use person.formattedBirthDate throughout our code.

So our constructor would look like this:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

...

this.birthDate = this.isValidDate(obj.birthDate) ? obj.birthDate : ''

this.formattedBirthDate = this.formatDate(this.birthDate)

...

}

}Likewise, if we want to show the person’s full name in the UI, we can create a function to get the fullName instead of writing that code everywhere that we want to use it in the UI.

class Person {

...

getFullName() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`

}

}If you are trying to optimize your code, then your models could help you conveniently manage a lot of those optimizations.

Adding properties to the model will cost you memory, but reduce your CPU usage since you won’t be calling functions to get the same value over and over. On the other hand, using functions will cost you CPU usage, but won’t saturate your memory space with different variations of the same data.

The best optimization strategies will often use a mix of both. For example, formatting dates can be very CPU expensive relative to the amount of memory it would cost to store the formatted date string. On the other hand, storing a person’s full name might cost more in terms of memory than it would in CPU usage to concatenate a couple of strings.

And it should go without saying that if the formatting function could potentially return different values every time it is called (such as containing time stamps, or counts, etc…) then you should always call the formatting function when you need to display its value.

Models Composed Of Models

It is quite common to have models that are composed of other models. It would be great if every model was composed only of primitives (number, string, etc…), but that is rarely the case in the real world.

Let’s take our person.address field for example. Chances are that this field won’t be a string, but it will be an object containing various data about the address.

class Address {

constructor(obj) {

obj = obj != null ? obj : {}

this.city = obj.city != null ? obj.city : ''

this.state = obj.state != null ? obj.state : ''

this.street = obj.street != null ? obj.street : ''

this.zipCode = obj.zipCode != null ? obj.zipCode : ''

this.fullAddress = this.getFullAddress()

}

getFullAddress() {

return `${this.street} ${this.city} ${this.state} ${this.zipCode}`

}

}And our Person constructor will now look like this:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

obj = obj != null ? obj : {}

this.address = new Address(obj.address)

...

}

}Notice that we do not need to null check the obj.address property in our Person model because the constructor for our Address model already has that null check built in to it. We can simply trust our Address model to give us something useful no matter what we create it with. And this should be true of all of our models! If we build them to be trustworthy for our code, then we only have to focus on using them correctly throughout our code.

Models With Arrays

You are inevitably going to have models that contain arrays. Sometimes they will be arrays of primitive values, and sometimes they will be arrays of other models.

In the case that your model has an array of primitive values - let’s use strings as an example - then you can either trust the input to be all strings, or loop over the array and type-check each value. If you opt for type-checking then you should only add things that either are strings or that can be converted to strings (e.g. things that do not return [object Object] from .toString()). If you trust the input, then assigning the array to your model looks the same as assigning a primitive value to your model:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

...

this.petNames = obj.petNames != null ? obj.petNames : []

...

}

}One of the difficulties of setting arrays, can be in using APIs that don’t always return an array when you expect them to. I’ve worked with APIs that would return null instead of an empty array, a single object instead of an array with one object in it, and an actual array only if there was more than one object to put in the array. Detecting if a value is null and setting it to an empty array in the model is easy enough. But what about detecting if, when it’s not null, you received an object or an array?

Enter the getArray function:

class Person {

...

getArray(objs) {

objs = objs != null ? objs : []

let array = []

if (Array.isArray(objs)) {

array = objs

} else {

array = [objs]

}

return array

}

}Now our assignment in the constructor would look like this:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

...

this.petNames = this.getArray(obj.petNames)

...

}

}Now we can rest assured that our calls to person.petNames.length, person.petNames.map, person.petNames.find, etc… won’t crash our UI.

And finally, how do we handle arrays of other models? If I get an array of models as input, I want to run all of those models through their respective constructors in order to make sure that they are all safe to use in my UI. But what if I have several arrays, each one with a different type of model?

Well, we can build a function to help us with that.

class Person {

...

getArrayOfModels(clazz, objs) {

objs = this.getArray(objs)

const models = []

for (const obj of objs) {

models.push(new clazz(obj))

}

return models

}

}Notice that we are taking in a parameter named clazz that is the constructor for the type of model that will be in this array. We can call new clazz(obj) to create a new instance of whatever model we passed in to the function.

Also notice that we are making sure that the input objs is actually an array by resetting it with our getArray function.

You might also want to check if each object is actually an instance of the model you are creating so that you don’t add a bunch of default instances of the model - say, if there are a lot of nulls in the array of objs.

class Person {

...

getArrayOfModels(clazz, objs) {

objs = this.getArray(objs)

const arr = []

for (const obj of objs) {

if (this.hasPropertyOf(clazz, obj)) {

arr.push(new clazz(obj))

}

}

return arr

}

hasPropertyOf(clazz, obj) {

const model = new clazz()

const modelKeys = Object.keys(model)

for (const key of modelKeys) {

if(obj.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

return true

}

}

return false

}

}I’m using a loose definition of “if an object is an instance of a model” by only requiring an object to have at least one field in common with the model. Basically, if the object has any information that the model can use, I want to use it. You might require the object to have all properties of the model in order for it to be useful for you. In that case you can just make a slight change to the implementation of the hasPropertyOf function (return false if hasOwnProperty returns false, otherwise return true) and call it something like isInstanceOf.

Now, let’s say that the person.friends property, which we see has a default value of [], is an array of People models. We would set that property in our constructor like this:

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

...

this.friends = this.getArrayOfModels(Person, obj.friends)

...

}

}Model Utils

Inevitably, our models are going to have things in common, like needing to validate and format dates and other inputs, and needing to set arrays of other models. So let’s look now at building a common place to put these functions - utils.

We could pull all of our reusable methods out into a single file, like this:

/** utils.js */

export formatDate(date) {

let formattedDate = ''

try {

formattedDate = new Date(date).toLocaleDateString()

} catch (err) {

console.error('ModelUtils.formatDate - Invalid date: ', date)

}

return formattedDate

}

export getArray(objs) {

objs = objs != null ? objs : []

let array = []

if (Array.isArray(objs)) {

array = objs

} else {

array = [objs]

}

return array

}

export getArrayOfModels(clazz, objs) {

objs = ArrayUtils.getArray(objs)

const array = []

for (const obj of objs) {

if (ModelUtils.hasPropertyOf(clazz, obj)) {

array.push(new clazz(obj))

}

}

return array

}

export hasPropertyOf(clazz, obj) {

const model = new clazz()

const modelKeys = Object.keys(model)

for (const key of modelKeys) {

if(obj.hasOwnProperty(key)) {

return true

}

}

return false

}

export isValidDate(date) {

let isValid = true

try {

let d = new Date(date)

isValid = d.toString() !== 'Invalid Date'

} catch (err) {

console.error('ModelUtils.isValidDate - Invalid Date: ', date)

isValid = false

}

return isValid

}But, as time goes on, the number of methods in this file could become quite large. So, we could take this one step further and define several different utility files, and let each one focus on one particular type of data. Like this:

/** array.utils.js */

export getArray(objs) { ... }

export getArrayOfModels(clazz, objs) { ... }/** date.utils.js */

export formatDate(date) { ... }

export isValidDate(date) { ... }/** model.utils.js */

export hasPropertyOf(clazz, obj) { ... }

export isInstanceOf(clazz, obj) { ... }And finally, we don’t have to, but we could bundle these different utility files under one main utility export file - like this:

/** utils.js */

export * from './array.utils.js'

export * from './date.utils.js'

export * from './model.utils.js'Then we can import the utils functions wherever we need them and use them like this:

import { getArrayOfModels } from './utils'

class Person {

constructor(obj) {

obj = obj != null ? obj : {}

...

this.friends = getArrayOfModels(Person, obj.friends)

}

}Model Testing

Writing unit tests for models is pretty straight forward, and mostly repetitive from model to model. That being said, if any part of your code should have 100% test coverage, it is your models. The more dependable your models are, and the more you depend on them, the more reliable the rest of your code will be as a result.

The main things you will want to test your models for are these:

- does an instance of the model have all of the properties you expect it to, and only those properties

- does the model assign all input values correctly

- assign only valid properties from the input object to the corresponding model properties

- assign default values for any invalid or undefined inputs

- create new instances of other models when it should

- not create new instances of other models when it should not (see hasPropertyOf above)

- create arrays correctly (even if the input is not an array)

- assign formatted data as expected (e.g. formattedBirthDate)

- does the model set all the defaults correctly when the input is:

- undefined

- null

- an empty object, or an object that does not contain any of the model’s properties

- do the model’s functions work correctly

- return expected values

- modify the model’s state as expected

- log errors when expected

- throw errors when expected

Think about it, if you could trust your models to have valid data at any point in your application:

- How much easier would it be for you to write and maintain your code?

- How much faster would you be able to find and fix bugs?

- How much cleaner would your code be?

Data Cleanup

One final point that I want to cover while we’re on this topic is the cascading effect that happens when we compose models of other models.

If I receive a JSON object from the server that represents a person, and the person uses the Address model for it’s address field, then I just have to pass the JSON object to the person constructor, and the person constructor will pass the corresponding address part of that object to the Address constructor. When this happens with complex models (composed of models that are composed of other models), it’s almost magical to see how a complex, dirty JSON object can get cleaned up into something that won’t break the UI, just by passing it to a model constructor.

We could use the Person model, for example, like this:

const person = new Person(server_response_json)

const fullAddress = person.address.fullAddressAnd be confident that person is defined, person.address is defined, and person.address.fullAddress is at least an empty string. How many null checks and how much display formatting code has this just removed from your application?

Conclusion

Models give us the ability to handle data that may or may not be suitable for our application, format that data to suit our various uses, and set default values that we can be confident will not break our application or confuse our users. And they allow us to minimize the amount of defensive code we need to write throughout our application for dealing with the otherwise unpredictable state of the data we are using, which means our code is leaner, cleaner, more maintainable, and easier to test.

Building applications using models is like building a house out of bricks. Each model is a solid, well-defined piece of the structure. If you are not using well-defined models in your code, how often do you have to wonder if the data you are working with is actually in a valid state for the code you are using it in? And how often do you get bug reports of things not working, only to find out that the error was caused by something being undefined, or null, or not being an array when it should have been?

The model architecture pattern is not to be thought of as something that you plan to implement sometime in the future. As demonstrated by the existence of many MV* architecture patterns, it is a default state of mind when approaching the development of any JavaScript application. If your project does not currently use this pattern, I highly recommend making the investment to shift it over. And certainly, for any projects you start in the future, no matter what they are, models should be among the first code you write.

Github

If you want to see a full example of a working utils library, I have a utils library that you can use and it’s on Github at https://github.com/bjanderson/utils.

As an example of how to use those utils - our Person model would look like this:

// person.model.js

import { getArrayOfModels, getDate, getObject, getString } from '@bjanderson/utils'

class Person {

constructor(o) {

const obj = getObject(o)

this.address = new Address(obj.address)

this.birthDate = getDate(obj.birthDate, '')

this.firstName = getString(obj.firstName)

this.friends = getArrayOfModels(Person, obj.friends)

this.lastName = getString(obj.lastName)

this.petNames = getArrayOfStrings(obj.petNames)

}

}In order to install them in your project you will need to add this to your .npmrc file:

@bjanderson:registry=https://npm.pkg.github.com

and then you can

npm install --save @bjanderson/utils